Flow State: 11+ Activities to Enter a Flow State of Mind

With many things in life ostensibly out of our control, it is easy to consider our fate as being determined by external factors.

However, consider times when instead of being driven by extraneous forces, you have felt in complete control of your actions – the master of your destiny!

The positive emotions that accompany such experiences can create such a sense of escapism, exhilaration, and enjoyment that it becomes a marker for how life can be.

This is what is meant by optimal experience or flow state – the subjective state in which a person functions at his or her fullest capacity with their attention so focused on a task, that factors such as fatigue and boredom do not interfere; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will participate for the sheer sake of doing it (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Flow state is losing yourself in the moment; when you find your abilities are well matched to an activity, the world around you quietens and you may find yourself achieving things you only dreamt to be possible.

What is a Flow State?

Flow state encapsulates the emotions experienced when an activity is going favorably – have you ever felt ‘in the flow’ or ‘in the zone’?

Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2005) conducted interviews with rock climbers, chess players, athletes, and artists in order to address the question of why people perform time-consuming or difficult tasks for which they receive no apparent extrinsic rewards.

The study concluded that respondents reported a similar subjective experience, one they enjoyed so much that they were willing to go to great lengths to experience it again – several respondents described a ‘current’ (or flow) that carried them along effortlessly throughout the activity.

The defining feature of flow state is the intense experiential involvement in moment-to-moment activity; it can only be achieved on the basis of an individuals’ personal effort and creativity (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

While research has primarily focused on the experience of flow within structured leisure activities such as sports, education and artistic pursuits (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2005), it is important to recognize its applicability to many other aspects of life including a route to wellbeing.

Fritz and Avsec (2007) looked at the relationship between dispositional aspects of experiencing flow and the subjective wellbeing of music students. Their findings confirmed that experiencing flow is an important predictor of subjective emotional wellbeing. Flow plays an important role in subjective wellbeing (Myers & Diener, 1995) and in the relationship between wellbeing and healthy aging (Ryff, Singer, & Dienberg Love, 2004).

Payne, Jackson, Noh, and Stine-Morrow (2011) explored the nature of flow in older adults and its role in cognitive aging. Their research indicated that older adults have the capacity to experience flow when cognitive capacity and intellectual demands are in synch and, as such, may be an important factor for theories of cognitive optimization, health recommendations, and programs of lifelong education.

Mills and Fullagar (2008) examined student engagement in learning and found that flow correlates positively with motivation, with highly motivated people experiencing high levels of flow. An activity engaged in with high enjoyment, motivation, and concentration can facilitate the subjective experience of flow (Bonaiuto et al., 2016).

Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2009) postulated that the flow state experience was comprised of eight key dimensions, these dimensions are broken down into the optimal conditions for entering flow and the characteristics of being in a flow state. So that we can better understand the factors associated with flow – and make this mental state more accessible – let’s look at these in more detail.

The optimal conditions for entering flow:

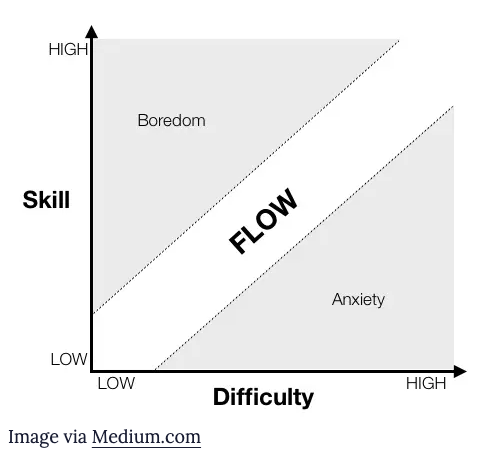

1. Challenge-skills balance

Flow state requires a balance between one’s skills and the challenge at hand: if the challenge is too demanding, we become disheartened and can experience negative emotions such as anxiety. Conversely, if a task is too easy, we become disinterested and indifferent – when we experience flow we are actively engaged but not overwhelmed by a challenge.

Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihalyi (1988) suggested this dimension occurs when the skills of an individual are at just the right level to manage the situational demands. The challenge–skills balance is a powerful contributor to flow, this ultimate sense of competence results in a state of engagement whereby a task is enjoyed through enthusiasm for the task itself (Elias, Mustafa, Roslan, & Noah, 2010).

2. Clear Goals & Unambiguous Feedback

To enter a flow state we must repudiate the sometimes conflicting demands of a task and focus on the next step. Having clear, well-defined goals fosters an understanding of what actions need to be taken to accomplish the activity at hand.

Mitchels (2015) found positive correlations between flow state and performance goals within both academic and athletic contexts. Receiving unambiguous feedback (often from the activity itself) allows us to constantly adjust our responses to meet the required demands.

While positive feedback can come from a variety of sources, the meaning is the same, i.e. information that one is succeeding in one’s goal (Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi, 1988).

Under these two conditions an individual can enter into the subjective state of flow, often exhibiting the following characteristics:

i. Action-awareness merging

In a flow state, we are completely absorbed in the here and now to the extent that involvement in an activity is so absolute, it becomes second nature – almost automatic.

Jackson (1992) analyzed the flow descriptions of athletes, finding that there was no real awareness of being separate from the action being performed, with some describing flow state as being “in the zone” or “in the groove”.

ii. Concentration on the task at hand

Total concentration or immersion is one of the most frequently mentioned flow dimensions. Focusing on the present moment allows us to better enter into a state of flow by directing our attention and enables us to circumvent superfluous distractions. In a flow state, we are fully engaged with an activity – only aware of what is relevant and dismissing unrelated factors.

iii. Sense of control

In flow, a sense of control is present without being consciously exerted. Rather than being ‘in control’, Csikszentmihalyi (1993) suggested this dimension is more of a ‘sense of control’ where individuals feel like they are unstoppable or feel like they can achieve anything.

The sense of exercising control in difficult situations is central to the flow experience; Keller and Blomann (2008) found that individuals with stronger control characteristics were more likely to experience flow, whereas individuals with weaker internal levels of control often failed to achieve a flow state.

3. Loss of self-consciousness

We can spend an abundance of time and energy monitoring how we appear to others, however, during flow any concerns for the self dissipate as we become one with the activity.

Put simply, in a flow state we are too involved in the moment to be concerned with protecting our ego – when freed from self-consciousness we can do things intuitively and with aplomb.

The absence of self-preoccupation allows us to shift our focus to the task at hand while rejecting extraneous and egocentric distractions.

4. Transformation of time

Have you ever been so immersed in something that you lose track of time? The experience of flow state can perceptibly distort our sense of the ordinary passage of time as we are completely absorbed in the moment.

A transcendence of time can occur when one is deeply involved in an activity, we can experience time as slowing down, speeding up, or in some cases, it becomes completely irrelevant (Hanin, 2000).

5. Autotelic experience

Autotelic experiences (endeavors carried out for their own sake, with no expectation of a future benefit, from the ancient Greek ‘autós’ meaning ‘self’ and ‘télos’ meaning ‘result/outcome/end’) are some of the most rewarding.

Csikszentmihalyi and Robinson (1990) examined receptive aesthetic experiences within museums; their findings suggested the consequences of deep and autotelic involvement are characterized by feelings of personal wholeness, a sense of discovery, and a sense of human connectedness. Within this setting, the intense involvement of attention in response to a visual stimulus was for no other reason than to sustain the experience.

This dimension is described by Csikszentmihalyi (1990) as the end result of being in a flow state, with potentially entropic experiences being transposed into flow.

6 Examples of Flow in Action

Flow state can be experienced in almost any activity that has clearly defined goals and a balance between the difficulty of the challenge and the skills of the individual.

While certain activities are likely to encourage a flow state, such as games, sports, and the arts, you can also experience flow within the workplace and other day-to-day activities.

Activities known to inspire flow are generally those in which you feel totally involved, do not experience boredom or anxiety, and in which you feel totally involved and interested. With this in mind, let’s look at some examples of flow in action.

1. Flow in Music

We have probably all, at some time, experienced a sense of complete absorption in an activity that involves music – whether the activity is listening to or playing music, it is a pursuit in which many experience intrinsic enjoyment.

Indeed, Chirico, Serino, Cipresso, Gaggioli and Riva (2015) noted a significant relationship between music and flow experience. Consider a musical performance, the orchestra knows exactly what they are doing in the moment – they seem to flow together, the players are completely absorbed in the music with their intense concentration allowing them to enter into a state of flow.

2. Flow in Sport

Have you ever experienced time going by quickly while playing a sport? Or been so completely absorbed in the game that afterward, you can’t really remember the details of what happened?

If you take part in a sport, whether it is athletics, mountaineering or golf, or it is likely that at some point you have entered into a flow state.

Reports of flow state within sporting activities are more common than in many other contexts, athletes frequently describe experiencing increased confidence through a sense of control and less self-consciousness as a result of their absorption in the activity (Hanin, 2000).

3. Flow in Gaming & Technology

For many, a flow state can be experienced through video games. Klasen, Weber, Kircher, Mathiak and Mathiak (2012) examined the flow state during video game playing. Their findings suggested the emergence of flow during gaming was in part due to the balance between the ability of the player and the difficulty of the game, concentration, direct feedback, clear goals, and control over the activity.

Furthermore, game designers Jenova Chen and Nicholas Clark developed a game called ‘Flow’ based on Csikszentmihalyi’s flow theory – wherein the game automatically adjusted its difficulty and reactions based on the actions (skills) of the player.

Through this personalized challenge-skills balance, less skilled players reported an increase in control over the gameplay that was necessary to feel more immersed in the game and to achieve flow.

Pilke (2004) studied the impact of flow experiences within the use of technology, indicating that flow is experienced frequently while performing a variety of technology-based tasks ranging from word processing, programming, visual design, and online searches.

4. Flow in the Workplace

Have you ever felt your work day was dragging by? You can’t stop watching the clock and an hour seems like five? Maybe you’ve experienced the opposite, where you have been so absorbed or challenged by a task that it’s suddenly home time?

Flow has many benefits within a workplace setting; a flow state encourages creativity and cultivates innovative thinking (Pearce & Conger, 2003). It may seem unlikely, but the workplace is not too dissimilar to training/playing sports or video games in that most places of work have goals, immediate feedback, and ideally, equip an individual with the skills required to complete a task.

5. Flow in Education & E-Learning

E-learning has become an important tool within educational institutions and businesses – engagement with e-learning tools can aid the negation of issues related to departmental budgets and the employment of trainers.

With this type of learning, we can assume that the setting of clear goals and working within your skill level is essential, in the absence of face-to-face training, individuals must self-regulate their concentration on the task at hand.

With this in mind, Choi, Kim, and Kim (2007) tested an e-learning success model based on flow theory to examine data from a web-based e-learning system. The results suggested there was a significant relationship between e-learning and flow experience, with flow playing a positive role in learning outcomes.

6. Flow in Hobbies

Have you ever lost track of time while reading a book? Or been so involved and focused on an activity, that you are unaware of anything else until you stop and gather your thoughts?

Hobbies are a prime example of autotelic activities; whether it is art, gaming, dancing, or sport, we all have something we are intrinsically motivated to participate in regardless of external rewards.

Taking a break from the mundane to engage in creative activities you find enjoyable can boost self-esteem, increase motivation, and enhance wellbeing (Burt & Atkinson, 2011). So why not reacquaint yourself with the joys of downtime, pursue a musical instrument, learn to knit, take up photography, or try your hand at writing?

7 Activities to Achieve a Flow State

As previously mentioned, the state of flow occurs under optimal conditions.

Individuals who achieve a flow state more regularly tend to pay closer attention to the details of their environment, seek out opportunities for action, set goals, monitor progress using feedback and set bigger challenges for themselves – Csikszentmihalyi (1990).

So what activities can you take part in to help achieve a flow state?

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) suggested achieving flow in the following ways:

1. Focus on the body

The body’s capacity for enjoyment is often overlooked, taking control of your physical capabilities and understanding your level of skill in an activity encourages an increase in confidence while simultaneously experiencing a loss in the self-consciousness barrier that often impedes entering a flow state.

Through practice and the development of skills required by an activity, we can find pleasure in our abilities while simultaneously receiving feedback through our successes or failures.

2. Focus your mind

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) suggested the normal state of the mind is chaos – it is relatively easy to concentrate when our attention is structured by external stimuli, however, when left to our own devices the mind reverts to a disordered state.

Our tendency to focus on the negative means it is important to gain control over our mental processes and steer our thoughts in a positive direction. Meditation is a great way to become more mindful, it quiets the mind by focusing attention and calming emotional interferences such as anxiety.

Through meditative practices, we increase mental awareness while at the same time decrease physiological tension (Belitz & Lundstrom, 1998).

3. Leverage memory

Leveraging memory can assist in flow state achievement, particularly if it involves recalling the fulfillment of a goal and the positive emotions that accompanied it. By taking some time to think about previous successes we can confidently assess our skills in relation to the difficulty of the task and set appropriate goals which meet the challenge-skill balance required to achieve a flow state.

4. Focus on your thoughts

Have you ever been so ‘lost in thought’ that time itself seemed to alter? Philosophy and deep-thinking flourished because we consider it to be innately pleasurable. We are motivated by the autotelic enjoyment of thinking rather than any perceived rewards that would be gained by it – by consciously focusing on our thoughts we can avoid distractions that may impede flow state achievement.

5. Communicate

Communication, whether through conversation or writing is another way of encouraging flow by improving our understanding of past experiences, writing, in particular, gives the mind a disciplined means of expression and self-feedback.

Observing and recording the memory of an experience fosters an understanding of our own capabilities, particularly in relation to the balance between the challenge in question and our level of skill.

6. Lifelong learning

The goal of learning is to understand what is happening around us and develop a personally meaningful sense of what one’s experience is all about.

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) suggests the end of formal education should be the start of a different kind of education that is motivated intrinsically.

The continuation of learning, whether it be within an educational institution or otherwise, allows us to develop an understanding of our skills and limitations which consequently assists our understanding of personal challenge-skills balance.

7. Focus on the job at hand

In the modern workplace, there is often an emphasis on productivity rather than wellbeing. People may consider their jobs as a burden foisted upon them, however, an employee who finds variety, appropriate challenges to skills, clear goals and immediate feedback within their job can find flow in the workplace.

The knowledge that goals are being achieved allows us to tailor our actions in order to meet the demands. There are ways we can approach work that alters our perception of the mundane and encourage a flow state.

You could try taking on a challenge you haven’t attempted before or ask your employer to trust you with an important task – by taking a calculated risk where you know your skills are suited to the task you can push your limits and achieve flow.

4 Exercises to Help Trigger a Flow State

As previously discussed, Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2009) suggested the optimal conditions for entering flow are the challenge-skills balance, clear goals and unambiguous feedback.

With this in mind, Sawyer (2015) and later, Kotler (2014) expanded on these dimensions of flow, suggesting that these are in fact just some of the ways in which we can trigger a flow state.

According to Kotler, flow can only arise when all of our attention is focused in the present moment and in order to focus our attention on the present we may need complete exercises to help trigger a flow state by guiding our attention to the here and now.

These flow state triggers suggested by Kotler can be divided into four categories:

Social: the collective flow or group flow happens when people enter a flow state together e.g. within a sports team.

Creative: thinking differently about the challenges you face and approaching them from a different perspective.

Environmental: external qualities in the environment that drive people deeper into ‘the zone’.

Psychological: internal triggers that create more flow.

Here we will examine these categories in more detail and suggest some exercises you can put into action in order to focus your attention and trigger a flow state.

1. Social Triggers

Flow state is more than just an individual phenomenon. Van den Hout, Davis and Weggeman (2018) noted the potential for group flow to enhance a team’s effectiveness, productivity, performance, and capabilities.

Social triggers are effective in shaping our social conditions and encouraging group flow. Intense concentration, clear group goals, and communication (including close listening) were encapsulated by the conditions proposed by Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2009) namely the challenge-skills balance, clear goals, and unambiguous feedback.

Kotler suggested that familiarity and equal participation – more specifically equal skill levels within the group – negate problems that may arise from disparity in team members’ abilities and ensures each member is on the same page.

An element of risk pushes our abilities further and acts as a means of focusing concentration, “There can be no genuine creativity without failure, which means in turn there can be no group flow without the risk of failure.” (Sawyer, 2015, p. 10).

Additional social flow state triggers include the blending of egos. In a group flow state, there is no room for a domineering ego, each member must merge their needs into those of the group while retaining their sense of control.

Finally, always say yes! In reality, this shouldn’t be taken literally rather it should be understood in terms of encouraging group interactions that are positive rather than argumentative in order to create momentum and amplify team ideas and actions.

Social Exercises:

Try making your group interactions more positive; a positive approach can encourage a feeling of togetherness. Say “Yes” to that new challenge and revel in it.

If you feel your skill level isn’t where it should be in relation to a task – practice! With familiarity comes confidence.

Take calculated risks and push your abilities to the very limit.

Be aware of the group goals, familiarize yourself with what is expected of you from others and focus on playing your part as best you can.

Speak up! If you are hesitant to voice your opinion or convey an idea – go for it. The elevated risk level of taking yourself out of your comfort zone is an effective flow trigger.

Listen! Try to engage fully in the moment by giving companions your undivided attention.

2. Creative Triggers

Kotler suggested that creativity can trigger flow and in turn, flow increases creativity in a positive feedback loop. We are hardwired to recognize patterns and are attracted to taking risks – combining the skill of linking new ideas with the confidence to present these ideas to others is liberating and a great way to trigger a flow state.

Creative Exercises:

Try taking a different approach when tackling a new challenge, really stretch your imagination, think outside the box and look at problems from a different angle than you would normally.

Raise the bar for yourself – allow yourself to believe you can do better. When you achieve your latest goal, set another!

Take a risk and trust that you will succeed – when you take a chance and it pays off, you encourage more of the same. Successfully tackling a problem nurtures your confidence, allowing you to believe in your abilities.

Immerse yourself in situations that would ordinarily be outside of your comfort zone, the unfamiliar encourages us to see things from a different perspective and come up with solutions we may not have previously considered.

3. Environmental Triggers

When an activity or task has some perceived physical, mental, social, or emotional risk (high consequences), it is important to navigate the potential risk and understand that consequences are relative.

Oftentimes, with risk comes reward – consider a mountaineer successfully scaling a dangerous summit, the elevated levels of risk drives him/her to their limit and deeper into a state of flow. Pushing yourself out of your comfort zone (but not so much that your challenge-skills balance is upset) will help you focus and achieve flow.

Likewise, a rich environment and deep embodiment (total physical awareness) in an activity can capture our attention through novelty, unpredictability, and complexity, whereby we learn through doing and by engaging multiple sensory streams at once. Routine may be the cornerstone of productivity, but it is not the cornerstone of flow (Kotler, 2014). The following exercises can help to foster an environment in which you are challenged to the point of reaching a flow state.

Environmental Exercises:

Immerse yourself in new experiences and environments – unpredictable situations make us pay more attention to what is happening in the moment. Why not try playing a new sport or joining a social group either online or within your local community?

Take part in activities that have high consequences for you personally – whether they are emotional, intellectual or social risks, try pushing yourself to achieve things you never thought possible. Never took part in a marathon before? Sign up! Too intimidated to speak up in that meeting? Clear your throat and go for it!

Take a walk – remove yourself from the familiar and immerse yourself in nature. Be mindful of your own body and movements to encourage complete physical awareness.

4. Psychological Triggers

We can trigger a flow state with psychological (or internal) prompts that hone our focus and allow for greater concentration in the moment.

Kotler (2014) suggested that flow requires extended periods of intensely focused attention, clear individual goals and immediate feedback so that we better understand what is expected of us (and if we have been successful), and a balance between your skills and the challenge. When engaging these psychological triggers, we lessen the potential extraneous factors that may impede flow.

Psychological Exercises:

Consider your skill level and set clear personal goals – take a few moments to think about what is to be done, try writing them down if it helps cement your objectives and get them clear in your mind.

Create your own personal mission statement – consider your abilities and targets and ask yourself, “What do I want to achieve?”

Don’t look for external validation instead rely on your own internal validation, the goals you have set and achieved are enough to legitimize your success.

Questionnaire for Measuring Flow

Over the past two decades, research into the occurrence of the flow state among employees in a work-based context has highlighted some significant positives, both subjectively in terms of elevated employee psychological wellbeing (Debus, Sonnentag, Deutsch and Nussbeck, 2014) and objectively in terms of enhanced job performance (Eisenberger et al., 2005).

Given the benefits of achieving flow, it’s important for practitioners in the positive psychology space to be aware of the key methods at their disposal for measuring an individual’s flow.

The Flow Questionnaire (FQ): Composed by Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihalyi (1998), the FQ poses three quotes which encompass the subjective experience of the flow state and ask respondents if they have experienced a similar state, if so – how often and under what circumstances, i.e., what activity were they engaged in.

Example quotes include:

“My mind isn’t wandering. I am not thinking of something else. I am totally involved in what I am doing. My body feels good. I don’t seem to hear anything. The world seems to be cut off from me. I am less aware of myself and my problems.”

“My concentration is like breathing I never think of it. When I start, I really do shut out the world. I am really quite oblivious to my surroundings after I really get going. I think that the phone could ring, and the doorbell could ring or the house burn down or something like that.”

“When I start I really do shut out the world. Once I stop I can let it back in again.”

Using a Likert-like scale, respondents then rate their level of agreement with expressions such as “I get involved” and “I enjoy the experience and the use of my skills” alongside expressions relating to the level of challenge posed and the subjective skill level of the respondent in the context of the challenge.

The respondents’ experience is then partitioned into one of three main non-overlapping states based on the model of flow state (figure 1) – flow, anxiety or boredom – with the flow state achieved when there is an equilibrium between the perceived challenges and the pertinent skill level held by the respondent.

Figure 1: Model of Flow State.

While the FQ has stood the test of time, it’s not without its critics. While the flow state model provides a clear unambiguous distinction between flow and non-flow (boredom and anxiety) states, Moneta (2010) suggested the state of flow could be categorized further into “deep” or “shallow” flow with the former distinguished by subjective perceptions of isolation from their immediate environment.

The Experience Sampling Method (ESM): The Experience Sampling Method represents the most common method used to assess flow. Individuals undertaking the ESM are required to fill out an experience sampling form (ESF) five to eight times a day over the course of a week. The ESF contains 13 categorical items (i.e., where, when, what are you doing, why are you doing it) to determine the context and motivational components of the challenge and 29 scaled items aimed at assessing the individual’s state of mind at the time.

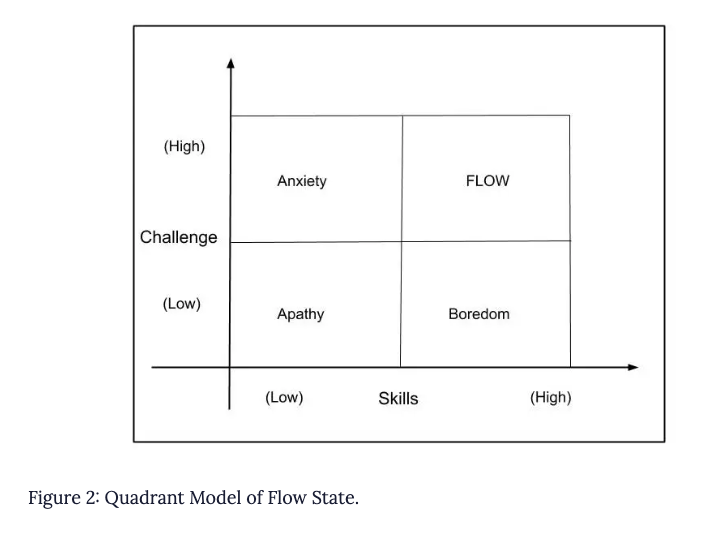

Based on responses, z-challenge and z-skill scores are calculated and categorized contextually (i.e., one individual may have a z-challenge score for work and another for leisure) with the quadrant model of flow state used to determine the individual’s state.

The notable difference between the quadrant model and the first model of flow state is the addition of the ‘apathy’ state, posited to be the most negative state of the four.

A robust approach to measuring flow, the ESM negates the risk posed by the FQ in its reliance on retrospective reconstruction of past events. However, the ESM has its own drawbacks with the most notable being that care must be taken to avoid biases when recording respondent data and that the request to complete an ESF can actually interrupt the flow experience (Moneta, 2010)

The Experience Fluctuation Model [EFM]: Proposed by Massimini et al. (1987), the EFM – also known as the ‘channel model’ or ‘octant model’ – further partitions the potential mental states into eight arc sectors. By encompassing a broader range of states while effectively narrowing the arc of the flow state, the model provides greater distinction between non-flow states while reducing the chance for false-positives – given the narrower flow arc.

While the model is different, researchers have combined the ESM with the octant model to effectively assess the flow experience in individuals with validation of the model achieved through the replication of findings across a range of demographics, cultures and life domains (Moneta, 2010).

Given the rising popularity of flow and flow state related literature it’s no surprise that researchers are finding and validating new approaches to assessing flow meaning that while robust measures such as those mentioned above exist, many less prominent methods are also accessible and are likely to be forthcoming as flow literature gains mainstream traction.

A List of Activities Known to Induce Flow

By this point, you are probably getting the hang of the concept of flow and the conditions in which a flow state can flourish. There are many activities that by their very nature compel an individual to focus their full attention on a task and present opportunities for all skill levels to be challenged yet achieve set goals. The following are just some of the activities you can embrace in order to induce flow in all aspects of your day-to-day life.

Swimming requires focus and practice, whether you are a novice or an adept swimmer, it opens you up to new challenges. If you are new to swimming or out of practice you might try setting smaller goals that challenge your skills, like swimming a full length. If you are a more experienced swimmer try to set a new personal best or complete more lengths than you’ve managed before.

Table tennis is a great activity to induce flow, much like swimming a player needs to be fully immersed and focused – if you can find an opponent who matches your skill level you will both avoid the negative impact of boredom and frustration.

Tai Chi is often referred to as meditation in motion and is known to enhance overall wellbeing and encourage a relaxed state (Sandlund & Norlander, 2000). Through physical action and the achievement of a meditative state our concentration is focused and our minds clear from distractions. Tai Chi grounds you in the moment and teaches you to control external interference, it is also ideal for people who prefer low impact activities.

Cycling and running (especially over long distances) are great activities to induce flow, intense focus on technique and pacing means that mental strength, physical strength, and physical ability is important.

Mountaineering and rock climbing can be considered extreme sports, there is a certain amount of danger involved, but in the spirit of flow, there’s no reward without a little bit of risk. While straying out of your comfort zone is an excellent way to enter a flow state, it is important to remember safety! Taking risks doesn’t mean putting your life at risk, it is enough to bring yourself outside of the mundane and into something challenging instead.

Osho Dynamic Meditation is an intense form of active meditation in which you must be continuously alert and aware throughout. Each meditation lasts for one hour and requires you to keep your eyes closed throughout, this forces you to concentrate fully on your movements and into a state of deep embodiment.

Cooking and baking are excellent ways to induce flow, once again, you must concentrate and focus your attention on the moment – allow yourself to be lost ‘in the zone’ and whip up some cupcakes!

If you are finding it difficult to induce flow, why not consider the Pomodoro technique? While this doesn’t work for everyone, those of us with a propensity for procrastination may find it a useful way to achieve focus in short bursts. The premise of this technique is simple: set a timer – usually for 25 minutes – and focus solely on your task intensely during that time. When the timer is up you should have a five-minute break before you set another timer. While some may find that this technique obstructs flow state through interruption, for others it helps gain focus and loosen up (Van Passel & Eggink, 2013).

These are just some of the activities you can get involved in that can help to induce a flow state; the important thing is to participate in an activity that suits your needs. In reality almost any activity you find intrinsically rewarding and that requires full engagement can guide you on the path to your flow state.

A Take-Home Message

Given the myriad benefits of achieving flow state across a broad range of contexts, including music, sport, art, and work, developing techniques to achieve flow affords us an exciting opportunity to work towards reaching our full potential and optimal levels of wellbeing.

You might already be familiar with the flow state but under a different name, i.e., ‘in the zone’ or ‘on form’. By clearly defining flow state it helps us to better understand the prerequisites for flow and in turn, identify methods by which we can enter the flow state and push ourselves to achieve our maximum potential.