Do People Drink Alcohol in Order to Regulate Their Emotions?

The idea that people drink alcohol in order to feel better has been around the psychological literature for at least 65 years. Between then and now, many theoretical models have incorporated this idea and many empirical studies have been conducted to test predictions associated with it. For the sake of the length of this post, here I will evaluate only the psychological theory; I will evaluate the empirical evidence in a future post.

It is non-controversial that people often report drinking in order to alter their affective state (i.e., in order to enhance the experience of positive emotions and to reduce the experience of negative emotions). However, that does not mean that a causal relationship between affect and alcohol use exists, as people do not always have conscious insight on their own behavior (but psychological research would be much more straightforward if they did!). Recently, I talked to many alcohol use researchers for a project of mine, and I noticed that they all have their own interpretation of the theories I am about to discuss. Indeed, all of these theories are verbal in nature, which means that they do not formalize their predictions in mathematical notation, and thus leave it up to the reader to translate them into testable hypotheses. While I will not go so far to formalize these predictions, following the ideas of Lakatos, I will attempt to identify the core assumption of these theories and derive specific and falsifiable auxiliary hypotheses from them (needless to say, these will come from my interpretation of these verbal models).

First, be aware that these theories I am about to throw together all have their own emphasis and unique predictions. Reviewing all of them in detail is beyond the scope of this post. Rather, I will focus on the similarities between them; as such, I am not discussing any of the theories in particular but rather their shared ideas more generally. Let’s call them the motivational perspective on alcohol use.

The main commonality I have identified in these models is that they assume alcohol use to be a behavior that is learned through reinforcement, specifically the reinforcement of affective change. Reinforcement theory dates back to B.F. Skinner’s famous work on rats and has been used successfully to advance our understanding of many psychological phenomena. Similarly, the early theories I have reviewed draw heavily on research performed on rodents. Reinforcement learning models have shown again and again that both animal and human behavior is motivated by rewards, which could either mean to obtain positive outcomes or to avoid negative outcomes. Thus, the idea here is that over time (which is unspecified, but this could happen over weeks, months, or years), people learn to associate the consumption of alcohol with positive affective outcomes (increased positive affect and/or reduced negative affect), which in turn makes it more likely that people respond to the need for affect regulation with alcohol.

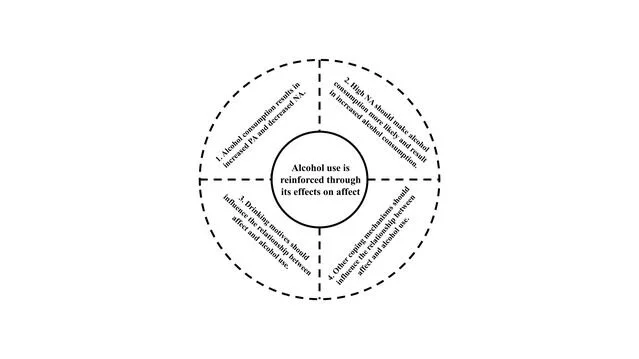

This idea, in its entirety, I consider to be largely untestable and thus unfalsifiable. Reinforcement learning has been applied successfully under laboratory conditions to understand phenomena in which the association between stimulus and response is learned in minutes or hours. As I mentioned above, the learning in alcohol use is likely to take place over a longer period of time in people’s natural environment. We simply cannot establish a causal relationship under these conditions. But that does not mean that the idea is useless or unscientific! Following Lakatos, we can consider the idea that alcohol use is reinforcing through affect regulation as the core assumption of these models. What we need in order to decide whether to retain, modify, or abandon the core assumption is a set of auxiliary hypotheses in which we break up the core assumption into several falsifiable pieces using concrete operationalizations. If we find support for these auxiliary hypotheses, our confidence in the core assumption increases. If we do not find support for them, we have a decision to make: Do we modify or abandon the core assumption, or do we modify our auxiliary hypotheses? That decision can only be made on a case-by-case basis depending on the insights obtained from the resulting studies. I will now discuss the four most important auxiliary hypotheses I have identified from reviewing the theoretical papers listed below.

1. Alcohol consumption results in increased positive affect and decreased negative affect. This is the low-hanging fruit. In order for alcohol use to be reinforcing through affective change, it needs to improve people’s mood during the time-course of its chemical effects in the body. This could either mean resulting in increased general positive affect and decreased general negative affect or it could mean that only specific moods are enhanced/reduced (e.g., anxiety rather than any negative emotional experience).

2. High negative affect should make alcohol consumption more likely and result in increased alcohol consumption.

This is the second hypothesis that can be derived from almost all of the models. Here are two reasons why we would expect this effect under the core assumption: First, when negative emotions are high, people will be more likely to want to regulate their emotions. If people learn to regulate their emotions via alcohol, then they should consume more alcohol at times where either general negative affect or specific negative emotions are intensely experienced. Related to this point, research in connecting areas has suggested that people become more impulsive when they are emotional, which might make them more inclined to fall back on a substance rather than other forms of coping. Second, if people weigh the decision to drink (vs not to drink) in terms of alcohol’s ability to make them feel better (which we know many people belief to be the case), they should be more likely to conclude that they should be drinking when they are feeling worse. I should mention that this hypothesis might be studied both between- and within-individuals and in several different ways (e.g., looking at total affect or variability in affect or change in affect; more on that in my next post).

Interestingly, the theories did not consistently expect positive affect to influence alcohol use; some suggested that positive affect makes people more social and alcohol more appealing, and hence people should consume more alcohol when positive affect is high in order to further enhance their positive emotions; others have suggested that positive affect reduces the need to regulate emotions (since people are already feeling good), and hence should result in decreased alcohol use; and then finally some models don’t discuss positive affect at all. As such, for now I am not including an effect of positive affect on subsequent alcohol use as one of the auxiliary hypotheses. But this might very well be one of the revisions I would consider once we have evaluated the evidence.

3. Drinking motives should influence the relationship between affect and alcohol use.

One thing I have not mentioned so far is that all of the theories emphasize that alcohol should not be reinforcing for every single person or in every single situation. They all point to genetic/biological, environmental, and individual psychological differences that should determine whether people ‘learn’ to drink alcohol in order to regulate their affect. I will discuss in more detail the implications of such expected heterogeneity in my subsequent post where I will go over the studies that have been and should be conducted, but for now I want to highlight one hypothesis that is strongly linked to the reinforcement idea. Several of the theories have pointed out the obvious that people don’t always drink alcohol when they’re feeling bad and that feeling bad shouldn’t be considered the only reason why people would drink. Thus, people’s motives or reasons to drink should have explanatory power; people should be more likely to drink when negative affect is high when the reason they report for drinking is to cope with said negative emotions (vs drinking for other reasons, for example a social occasion). Again, this hypothesis can be studied both between- and within-individuals.

4. Other coping mechanisms should influence the relationship between affect and alcohol use.

This is an interesting idea I saw infrequently raised, namely that if alcohol use is reinforcing by helping people to cope with negative affect, then the relationship between negative affect and subsequent alcohol use should be stronger when other coping mechanisms are not available to people. In other words, if people do not have other means to regulate their affect, this should not necessitate alcohol use, but simply make it more likely to be selected (and over time reinforced) as a coping strategy.

Core assumption/auxiliary hypotheses

Source: Jonas Dora

There are multiple other very interesting ideas in these rich papers (e.g., regarding the effects on the first drink of the night vs subsequent drinks, differences in predictions between alcoholics and non-alcoholics, the way deprivation and withdrawal might support the reinforcement learning process, …), but I will end it here for now. One thing I was surprised by was the high variability in researcher’s thoughts on the role of positive affect in the reinforcement of alcohol. In summary, I believe that it is possible to derive multiple falsifiable and rigorous auxiliary hypotheses from the core assumption that alcohol use is a behavior that is reinforced through affective change. In my next post, I will discuss the extent to which these hypotheses have been addressed by empirical research and should be addressed in the future.