Can Humor Make You a Better Leader?

I research leaders who have passionate hobbies, and I recently zoomed in on the “comedians” category: managers who do standup comedy or improvisational theatre in their spare time. They believe that their hobby is also making them better leaders.

In this, they are not an exception; all leaders I spoke with—including a CEO who makes grandfather clocks in his garage—said the same about their passionate pursuits. (If you really want to know, making grandfather clocks compensates for what you lose when, as a leader, you no longer produce something yourself but only through others; this compensatory mechanism further translates into psychological well-being in the leader role. In other words, when you become a top leader, making grandfather clocks keeps you from going cuckoo). But even compared to other hobbies, the case for comedy as a leadership booster looks particularly strong.

Humor is becoming recognized as an essential leadership skill. Yes, much of the research on leader humor reads like high voltage signs: Danger of shutting down colleagues! (Holmes & Marra, 2022); Beware of signaling that misbehavior is acceptable! (Yam et al., 2018) Or—leaders’ worst nightmare—diminished authority ahead! (Bitterly et al., 2017).

Still, a wave of new research recognizes that, risky though humor may be, leaders have got to have it. Funny managers are trusted more (Karakowsky et al., 2020) and are seen as better leaders (Cooper et al., 2018). They foster employee creativity (Huang, 2022), increase work engagement (Neves & Karagonlar, 2020), make change feel more manageable (Choi et al., 2022) and newcomers more welcome (Kang et al., 2022).

Getting humor right requires knowing how to create it, choosing your style, and knowing when to use it. Here is what academic research and funny managers advise on these three topics:

1. Creating humor

Take it seriously, like you would any other important skill. Take a course, read books, practice. There is little research on how to develop humor and it tends to cluster around Paul McGhee’s "7 Humor Habits Program" (Olah et al., 2022; Ruch et al., 2018). You may want to look for a course based on McGhee’s program or check out other "humor boot camps" available online or in person. Read Peter McGraw’s Shtick to Business (and watch him try to make an “unfunny” brewery owner become funnier) and HBP’s “What educators can learn from comedians” (one of the rare articles that actually deconstruct how to build a joke). Play an improvisation game with friends and family.

For a deeper dive into joke creation, read chapters 4 to 6 of Comedy Writing for Late-Night TV by three-time Emmy award winner Joe Toplyn. Take a standup or an improvisation class. From standup, you will learn how to read your audience, how to stay authentic, and how to look at the world around you with fresh interest. From improvisation, you will learn how to really listen to your interlocutor instead of planning your next line; how to step into other people’s shoes before deciding whether you agree with them or not; how to enjoy the team’s creativity instead of pushing your own ideas. All of these lessons are useful for leadership more generally (Moreira et al., 2022; Trepanier & Nordgren, 2017) and not just for getting you a good laugh.

Source: Emilia Bunea

2. Crafting your humor style

Research divides humor styles into four categories: First, affiliative style, humor that includes the others (“We delivered the project. Here’s to the company’s best midwives!”). Then, self-enhancing style, picking yourself up when things are tough by finding the fun in it all (“Darn, I lost this customer. Well, someone will find him eventually”). Third, self-defeating style, putting yourself down (“I provide invaluable lessons in bad leadership”), and fourth, aggressive style (“What kind of training did you get? Potty training?”).

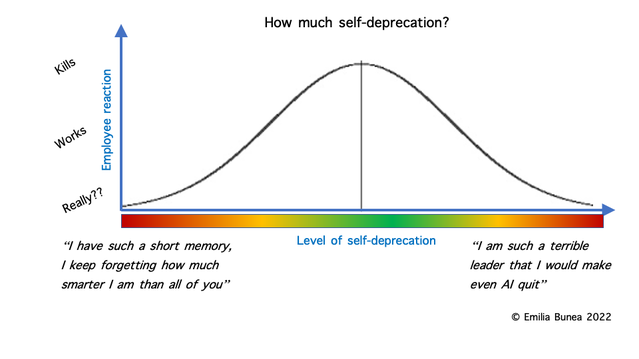

As a rough rule for leaders, use affiliative and self-enhancing humor and stay away from self-defeating and aggressive styles (Neves & Karagonlar, 2020). Wait, what about self-deprecating humor? While self-defeating humor is… well, self-defeating, its dialed-down self-deprecating version is very effective and even, some say, mandatory for leaders (Gkorezis & Bellou, 2016). See the “self-deprecating style” chart for a quick reference on how to kill by positioning your humor between a complete lack of self-deprecation and a full self-defeating meltdown (before you get called to HR, “kill” is meant in the comedic sense).

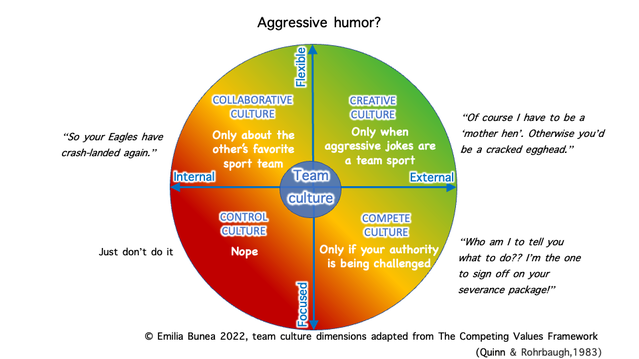

Is aggressive humor always bad in leadership? Some companies or teams have a culture in which punching each other with punchlines is a sport, and everybody is game (including the boss). This more often happens in less hierarchical and more creative teams.

As a leader, you’ve got to hold your own in such a culture (Terrion & Ashforth, 2002). Just know your own strength, as the leader role still comes with some extra power: don’t punch anyone unconscious. By contrast, if you’re in a highly hierarchical, “control” culture, it’s almost never a good idea to flex your aggressive humor style, as it may create irreparable damage. Refer to the “aggressive humor” chart… or else.

Source: Emilia Bunea

3. When to use humor

If you’re new to using humor as a leader, you’ll understandably want to start small. You’ll try it out during pre-meeting banter, for instance, not during that meeting about bad sales results. You won’t deploy it fully before you’ve gained some trust from your team.

Still, the most effective and transformative leader humor is often expressed in the riskiest situations. Here’s one I witnessed when I was CFO of a healthcare company:

In a progress meeting on building a new hospital wing, the project manager brought dire news: the passageway between the new and the old wing was one inch too low, and ambulances could not go through. I started running numbers in my mind; this would mean serious rework and budget overruns.

There was a moment of silence while everyone was busy panicking, until the operations director mused: “Have you tried Vaseline?” The roar of laughter that followed defused the tension and allowed the team to start brainstorming on creative ways to solve the problem instead of competing on who best deflects the blame. That joke became legendary in the company. But had the CEO, who was also present, frowned instead of joining in the Vaseline-induced laughter, the Ops director’s rise to the top would have needed a great deal more lubricant.

Finally, a recent study (Rosenbusch et al., 2022) found that how a joke lands depends much more on the audience than on the quality of the joke. If no one seems to realize you were joking, fire the least receptive team member on the spot; you’ll be surprised at how quickly the remaining members’ sense of humor will improve.